Major evacuation (‘Operation Pied Piper’) began in September, 1939. By February 1940 the small village of Barnack had taken 80, but the Government wanted the villagers to take another 200!

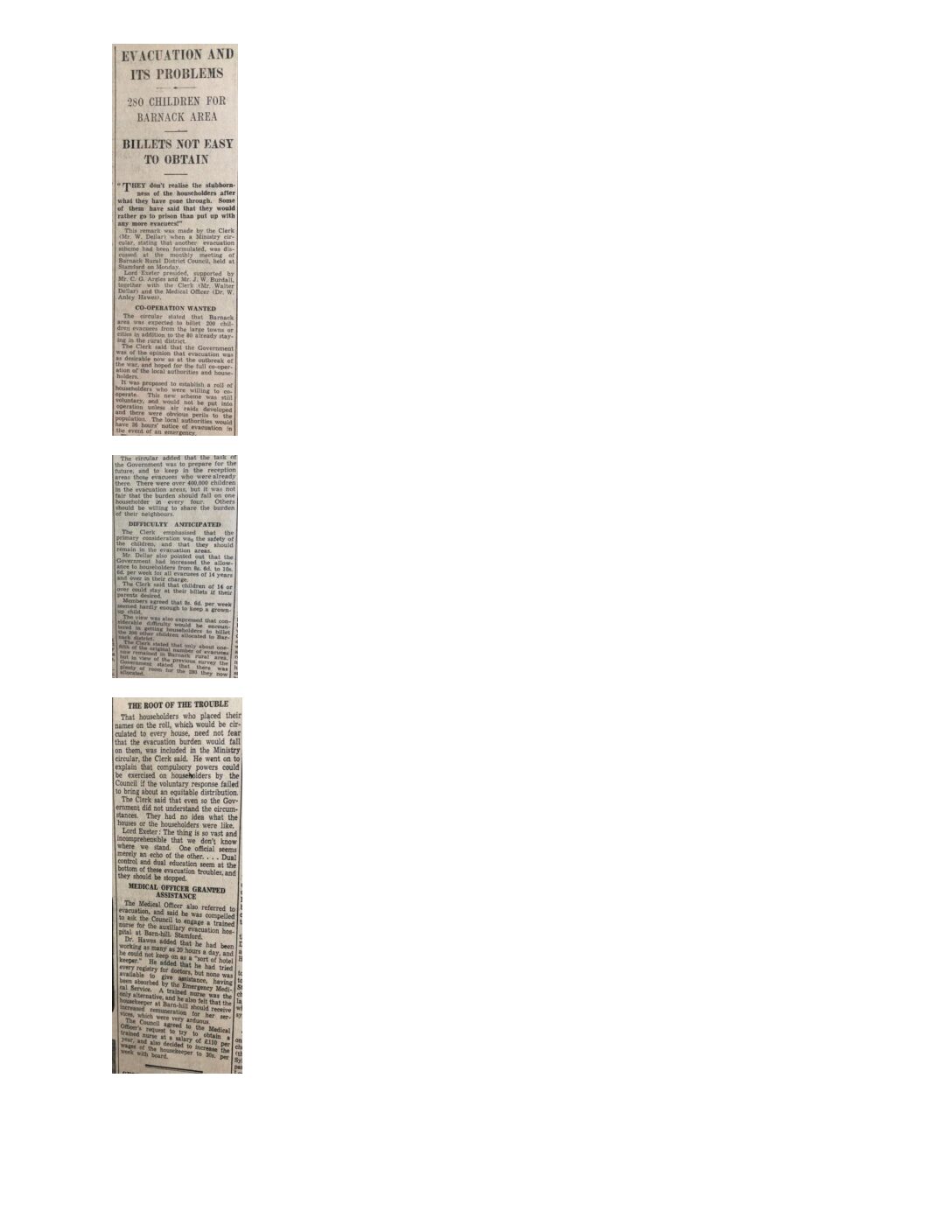

“280 CHILDREN FOR BARNACK AREA

Billets not easy to obtain.

‘They don’t realise the stubborness of the householders after what they have gone through. Some of them have said that they would rather go to prison than put up with any more evacuees!’

This remark was made by the Clerk (Mr. W. Dellar) when a Ministry circular, stating that another evacuation scheme had been formulated, as discussed at the monthly meeting of Barnack Rural District Countil, held at Stamford on Monday.

Lord Exeter presided, supported by Mr. C. G. Argles and Mr. J. W. Burdell, together with the Clerk (Mr. Walter Dellar) and the Medical Officer (Dr. W. Anley Hawes).

CO-OPERATION WANTED

The circular stated that Barnack area was expected to billet 200 children evacuees from the large towns or cities in addition to the 80 already staying in the rural district.

The Clerk said that the Government was of the opinion that evacuation was as desirable now as at the outbreak of the war, and hoped for the full co-operation of the local authorities and householders.

It was proposed to establish a roll of householders who were willing to co-operate. This new scheme was still coluntary, and would not be put into operation unless air raids developed and there were obvious perils to the population. The local authorities would have 36 hours’ notice oif evacuation in the event of an emergency.

The circular added that the task of the Covernment was to prepare for the future. There were over 400,000 children in the evacuation areas, but it was not fair that the burden should fall on one householder in every fout. Others should be willing to share the budren of their neighbours.

DIFFICULTY ANTICIPATED

The Clerk emphasised that the primary consideration was the safety of the children, and that they should remain in the evacuation areas.

Mr. Dellar also pointed out that the Government had increased the allowance to householders from 8s. 6d. to 10s. 6d. per week for all evacuees of 14 years andover in their charge.

The Clerk said that children of 14 or over could stay at their billets if their parent desired.

Members agreed that 8s. 6d. per week seemed hardly enough to keep a grown-up child.

The view was also expressed that considerable difficulty would be encountered in getting householders to billet the 200 other children allocated to Barnack district.

The Clerk stated that only about one-fifth of the original number of evacuees now remained in Barnack rural area, but in view of the previous survey the Government stated that there was plenty of room for the 280 they now allocated.

THE ROOT OF THE TROUBLE

That householders who placed their names on the roll, which would be sirculated to every house, need not fear that the evacuation burden would fall on them, was included in the Ministry circular, the Clerk said. He went on to explain that compulsory powers could be exercised on householders by the Council if the voluntary response failed to bring about an equitable distribution.

The Clerk said that even so the Government did not understand the circumstances. They had no idea what the houses or the householders were like.

Lord Exeter : The thin is so vast and incomprehensible that we don’t know where we stand. One official seems merely an echo of the other . . . .Dual control and dual education seem at the bottom of these evacuation troubles, and they should be stopped.

MEDICAL OFFICER GRANTED ASSISTANCE

The Medical Officer also referred to evacuation, and said he was compelled to ask the Council to engage a trained nurse for the auxiliary evacuation hospital at Barn-hill, Stamford.

Dr. Hawes added that her had been wroking as many as 20 hours a day, and he could not keep on as a ‘sort of hotel keeper.’ he added that he had tried every registry for doctors, but none was available to give assistance, having been absorbed by the Emergency Medical Service. A trined nurse was the only alternative, and he also felt that the housekeeper at Barn-hill should receive increased remuneration for her servcies, which were very arduous.

The Council agreed to the Medical Officer’s request to try to obtain a trained nurse at a salary of £110 per year, and also decided to increase the wages of the housekeeper to 30s. per week with board.”

The Stamford Mercury, 23rd February, 1940.